Bringing History to Life in Minnesota

Dr. Maddalena Marinari is an assistant professor in History; Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies; and Peace Studies at Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota. Her 18 students have submitted over 100 articles to the History Unfolded database, mostly from newspapers printed in "The Land of 10,000 Lakes." In this guest post, Dr. Marinari describes the impact the project has had on her and her students.

Here's Dr. Marinari:

A Perfect Match

Dr. Maddalena Marinari, professor at Gustavus Adolphus College.

A year ago, as I was putting the final touches on a syllabus for a mid-level history course on the domestic experience of the United States during World War II, I wanted to come up with an assignment that got my students into the archives but also exposed them to the local experience of World War II. When I read about the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s History Unfolded Project, I knew I had found exactly what I was looking for, but the rewards in the classroom surpassed by far even my more optimistic expectations. Although only a small number of students in the course were history majors, all of them embraced what one of them called an “opportunity to explore history in a hands-on setting working with real primary documents that had been largely forgotten.” The assignment asked them to choose one of the topics listed on the museum’s website, identify at least 10 articles on the subject, and place them in the context of the existing literature of what Americans knew about the Holocaust as it was happening.

Bread and Butter

Gustavus Adolphus College in St. Peter, Minnesota. Gustavus Marketing and Communication Office

Because we are a liberal arts college in rural Minnesota, many students initially doubted that they would be able to find much, but for many of them, according to another student, “it was very eye-opening to see how much our local newspapers actually reported about World War II topics.” Even more exciting, since many of the students in the class were from Minnesota, they had the opportunity to research what their hometown published about the Holocaust. One of them even found an article about his best friend’s grandfather! For one student, the project was even more personal: “Our work with the Holocaust Museum also allowed me a chance to connect with my Jewish heritage in a new way and gain some understanding on what it must have been like to view the Shoah from the perspective of an American Jew.” Another student told me that she repeatedly woke up in the middle night with ideas about other places to look for news, new key words to use in the databases of the digitized newspapers available, or new secondary literature to consult.

Some Surprises

There were also many surprises. A student who had chosen to work on Charles Lindbergh’s “Un-American” speech and was convinced that he would find a plethora of articles on the topic since Lindbergh was from Minnesota could barely find any newspaper reports, perhaps a reflection of Minnesota’s ambivalence towards its Jewish residents. Others expressed disbelief at how many articles they found, especially after reading in the secondary literature that Americans knew little about the Holocaust as it unfolded. Many of the students observed that they were shocked to see some of the newspapers’ efforts to justify what was happening to European Jews.

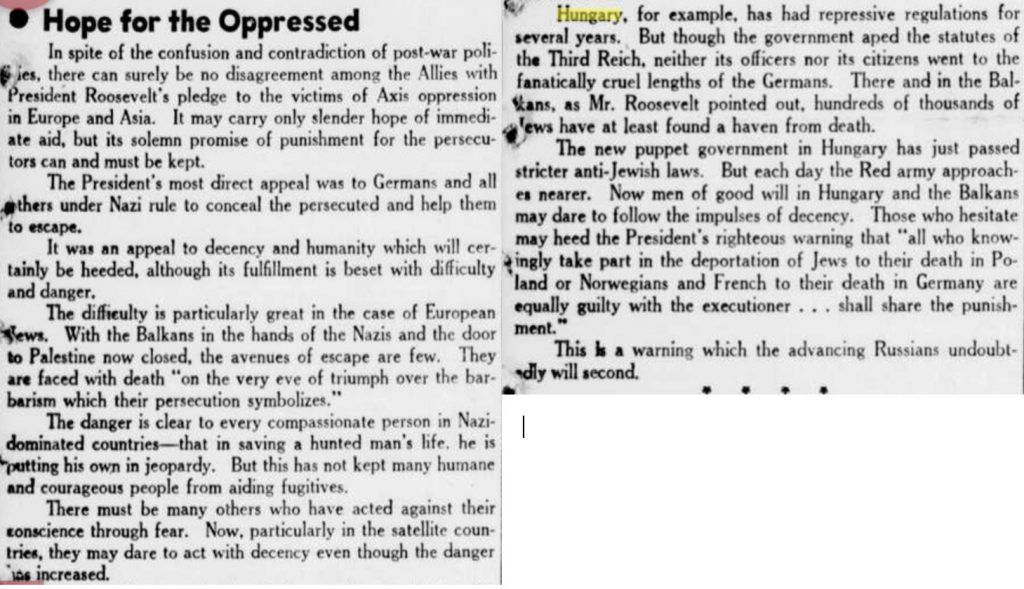

Izaak H. found this 1944 editorial on the plight of Jews under the Nazi regime. "Hope for the Oppressed." Brainerd Daily Dispatch. 1944-04-03

Rewards

Without a doubt, what students liked the most about the project was the opportunity to work with primary sources and help write history. For a lot of the students, contributing to a nationwide project gave them additional motivation to keep looking for sources, especially when they struggled to find news articles at first. As one student put it, “I also think it is very cool that we are able to put our findings in something as big as the Holocaust Museum in Washington D.C.” Perhaps the most rewarding aspect of the assignment were the insights about the period that students offered as they did their research. Rather than focusing exclusively on what the newspapers said (or didn’t) about the Holocaust, many of them wanted to put their findings in context, so they looked at the cartoons, at “the ridiculous number of ads” in the newspapers, or at the length of the articles about the Holocaust compared to those about other aspects of the war or daily life during the war. Many expressed surprise at how short or buried many of the articles they found were, especially compared to sizable articles (and cartoons) devoted to Mussolini, farm reports, or the latest fashion trends.

Helping Hands

From a pedagogical perspective, I was particularly excited to see how my students made the research for this project social and collective. Because of the different level of skills and the broad range of majors, I worked with our college archivist, Jeff Jenson, to hold three class meetings in our library so that students could learn how to identify their sources, request microfilms through interlibrary loan, and operate a microfilm machine. These meetings became crucial for their search and analysis of sources. When one of them struggled to find sources or ran into problems with the microfilm machine, there was always classmate who suggested a solution, proposed a new resource, or had a word of encouragement. Because this was a collective effort, many of them worked “that much harder to find articles” when faced with a roadblock. A student became so engrossed by the project that she continued ordering microfilms even after she had already found the ten sources required for the assignment.

The Real Deal

In addition to helping students think critically about the scholarship on what Americans knew about the Holocaust and getting them into the archives, I had one last hope for this assignment. At a time when the humanities are under close and constant scrutiny for their “real-world” value, I wanted my students to put into practice the skills and knowledge they learned in the classroom and see how historians can have an impact on the community and the world outside of the school. A student who is now pursuing a career in public history wrote that for her “the fact that the assignment gave us a look into one of the many ways that a history major could utilize their skills in a real world situation was amazing.” I could not have said it better myself.

[From Eric: See all the great work coming out of Minnesota here.]