Massive March on Washington Planned

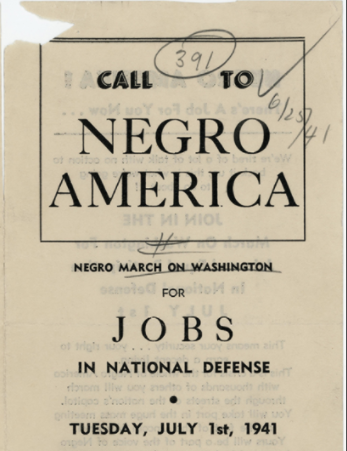

Demanding equal access to defense jobs and desegregation of the military, A. Philip Randolph launched the March on Washington Movement.

View newspaper articlesDomestic concerns in the United States, including unemployment and national security, combined with prevalent antisemitism and racism, shaped Americans’ responses to Nazism and willingness to aid European Jews. The economic devastation of the Great Depression, combined with isolationist attitudes and deeply held prejudices against immigrants, limited Americans’ willingness to welcome refugees. Many issues that the American public perceived as having a critical impact on their livelihoods, security, and core values vied for public attention during this time and affected the manner in which Americans responded to events at home and abroad.

With the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, the Roosevelt administration began to invest heavily in defense industries creating hundreds of thousands of new jobs. Within a few years, unemployment had plummeted among whites. However, the US army remained segregated, and the infusion of federal tax dollars in the economy benefited few if any blacks. Many defense contractors simply would not hire black workers regardless of their skills.

On January 25, 1941, at a meeting of African American leaders in Chicago, A. Philip Randolph, head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, seized upon a suggestion that blacks should march on the White House demanding that the President desegregate the military and provide equal access to jobs in the defense industry. He called for a massive demonstration in the nation's capital on July 1, 1941. Randolph’s network of labor connections mobilized efforts in African American communities across the country; the NAACP, Urban League, and black fraternities and sororities threw their support behind the march. The campaign captured the imagination of the community, and grassroots support for the March on Washington Movement (MOWM) spread like wildfire.

On June 3, 1941, Randolph sent letters to the President, Eleanor Roosevelt, and the secretaries of War and the Navy inviting them to address the marchers. Worried that the march would disrupt national morale on the verge of America's likely entrance into the war, and fearing a potential race riot, Roosevelt asked his wife, New York mayor LaGuardia, and several white civil rights leaders to intervene. Randolph, however, insisted that unless the President desegregated the Army and provided equal access to defense jobs, the demonstration would take place. By late June, newspapers predicted crowds topping 100,000 to march on Washington.

Quietly, moderate black leaders pushed Randolph to cancel the march. They were hesitant to damage relations with Roosevelt who, among other things, had appointed 43 African Americans to government positions. A week ahead of the march, Roosevelt negotiated with Randolph and NAACP head Walter White. On June 25, 1941, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, creating the Fair Employment Practices Committee, which had authority to investigate and end discrimination in defense industries, federal agencies, and unions. Though many in the movement wished to continue with the march, Randolph agreed to call it off. The executive order had limited effect in the defense industry, and the US military remained segregated. However, the March on Washington Movement set an important civil rights precedent and galvanized the community for ongoing struggle. Twenty-two years later, in 1963, A. Philip Randolph continued his struggle for jobs and freedom. He again organized a March on Washington that would be one of the largest political rallies for human rights in US history.

Learn More about this Historical Event

- 1941 - Plans for a March on Washington (FDR Library)

- American Memory: African American Odyssey (Library of Congress)

- Patriotism Crosses the Color Line: African Americans in World War II (The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History)

- The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow (PBS)

- FDR, A. Philip Randolph and the Desegregation of the Defense Industries - Lesson Plan, grades 9-12 (The White House Historical Association)

- Global Nonviolent Action Database (Swarthmore College)

Bibliography

Bracey, J.H, and Meier, A. “Allies or Adversaries?: The NAACP, A. Philip Randolph and the 1941 March on Washington.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly. Vol. 75, No. 1 (Spring 1991), pp. 1-17.

Kersten, Andrew Edmund. A. Philip Randolph: A Life in the Vanguard. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007.

Pfeffer, Paula F. A. Philip Randolph, Pioneer of the Civil Rights Movement. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1990.

Morehouse, Maggi M. Fighting in the Jim Crow Army: Black Men and Women Remember World War II. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000.

Weir, William. The Encyclopedia of African American Military History. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2004.

Search tips

These dates and keywords are associated with this historical event.